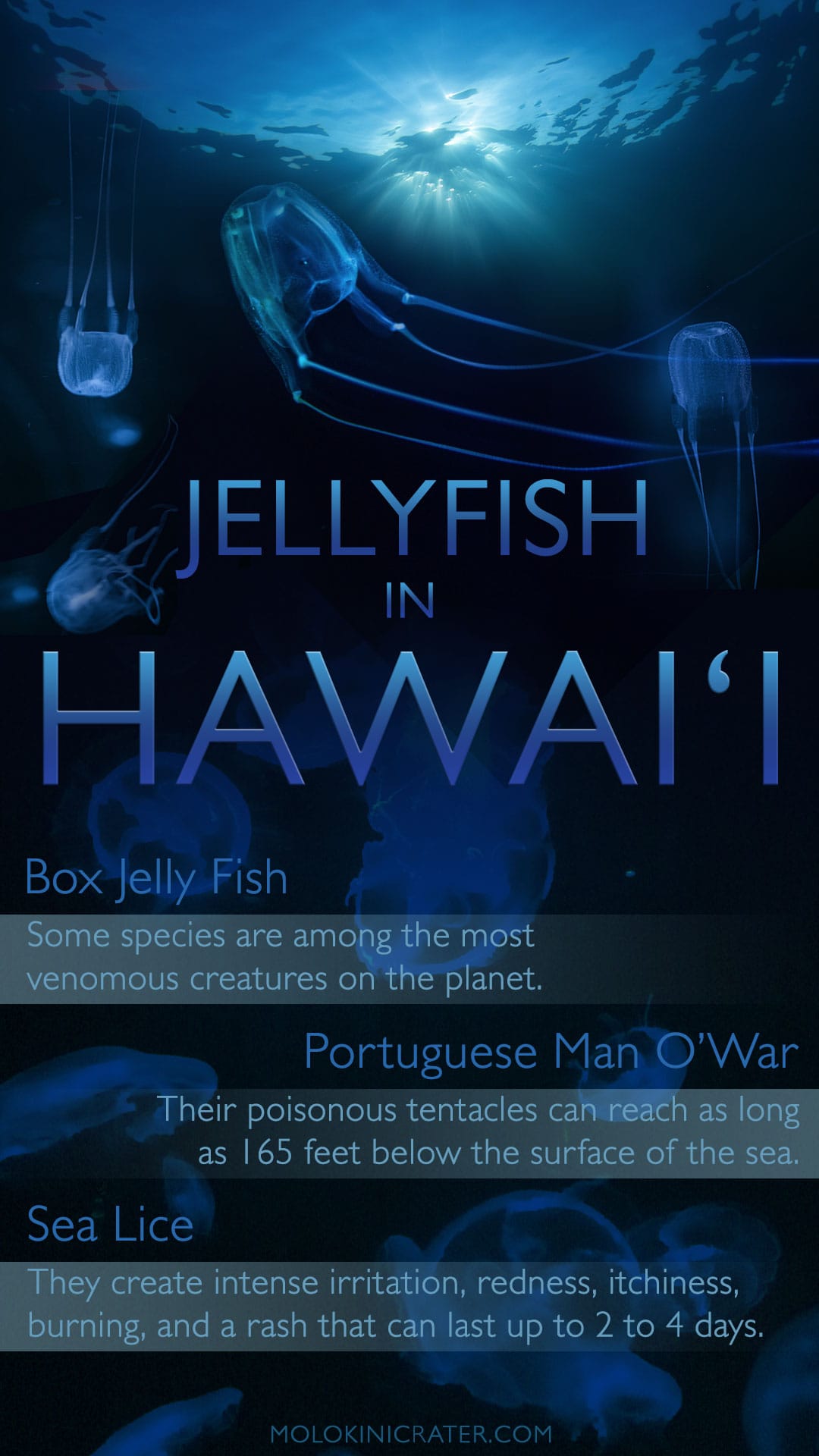

Jellyfish Stings, Portuguese Man O’ War Bites, and Sea Lice:

What to Know While Vacationing in Hawaii

Beachgoers are often floored by the gorgeousness of Hawaii’s waters. And who can blame them? Few places in the world are as warm and pristine, while the fun the Pacific affords can’t be beaten.

If you are stung, contact Modo MD for mobile Maui urgent care services. They’ll show up at the beach you’re on and treat you quickly. (888) 663-6631

But beauty isn’t exactly tantamount to worry-free. Injuries, drownings, shark attacks, wiping out on a rogue wave—locals and visitors alike are vulnerable to the dangers of the sea. Chief among them? Jellyfish stings, Portuguese Man O’ War bites, and sea lice—all of which can take a day from epic to miserable faster than you can say ouch.

Here’s what to stay mindful of the water in Hawaii—and how to remedy the situation fast if you find yourself harmed:

Box Jellyfish

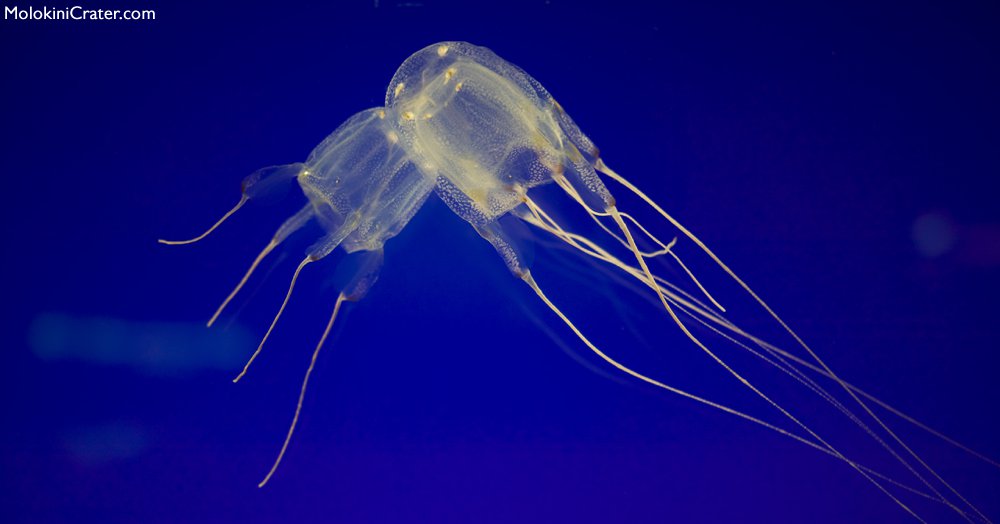

Bell-like and ethereal, Hawaii’s three species of box jellyfish are splendors to behold—at least in front of a plane of glass at one of the islands’ aquariums.

Up close, their mystique is certainly startling—such interesting shapes, such stunning colors—but not necessarily in a good way: While box jellyfish stings are rarely fatal, they are potent and painful (indeed, some species are among the most venomous creatures on the planet). This is due to their long tentacles, which are lined with stinging cells, known as nematocysts, that are typically used for feeding and seizing prey.

The largest of Hawaii’s three species, C. alata, are the fastest swimmers among jellies and their kin. They’re also active predators—and stings by them can be downright agonizing. When their nematocysts are activated, by touch or chemical cues, they fire a “barbed thread” that can pierce the skin and deliver toxins called porins, which, according to PBS, “are structurally similar to the blood-destroying, pore-forming molecules released from anthrax and streptococcus.” The result? A burning sensation, and, for some victims, more brutal reactions, including cardiovascular collapse.

Where they’re found:

Shallow waters—particularly in bays and estuaries—and over sandy-bottomed shorelines. Box jellyfish are generally sighted in Hawaii seven to eleven days after a full moon.

How to avoid them:

Scan shallow waters before getting into the water—especially a week after the full moon and during windy weather, as gusts can bring jellyfish closer to the shore—and heed warning signs. You can also check out the University of Hawaii/Waikiki Aquarium’s Box Jellyfish Calendar.

What to do if you’re stung:

Rinse the area with vinegar (contrary to popular belief, stings should not be rinsed with seawater, says assistant research professor at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and John A. Burns School of Medicine Dr. Angel Yanagihara). Then, apply heat, not ice; the latter may boost the venom’s activity and cause more than double the damage. Stings can also be treated with Sting No More, a venom-inhibiting product developed by Yanagihara with a grant from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Defense. Victims who have difficulty breathing, heart palpitations, cramps, and vision problems should be seen by a medical professional immediately.

Portuguese Man O’ War

Dubbed “bluebottles” due to their bluish-purple air bladders, Portuguese Man O’ War are part of a “wind-drift” group of sea organisms that are not a jellyfish but what’s known as a siphonophore—a colonial form that’s made up of individual polyps that give it the appearance of a single creature.

Sound spooky? It rather is: The gas-filled sac that supports the colony possesses a ridge that operates as something of a sail, allowing them to float on the surface of the ocean. (As the University of Hawaii reports, “Early explorers thought its shape resembled the helmets worn by Portuguese soldiers,” thus giving them their name.) Meanwhile, their poisonous tentacles—which deliver a powerful, very painful sting—can reach as long as 165 feet below the surface of the sea.

Where they’re found:

South-facing Hawaii beaches are the most likely places to encounter “bluebottles.” Invasions are tied in part to the weather, in that trade winds can carry them across the ocean and towards the shore—sometimes in packs of 1,000 or more.

How to avoid them:

Ditto to what’s advised under Box Jellyfish: Check the shoreline (water and sand) and keep an eye out for signs; also keep an eye on the news. Keep in mind that Portuguese Man O’ War’s translucent appearance can make them hard to see in the open ocean. What’s more, those that wash up on Hawaii’s beaches (even dead ones) may still be able to sting. To phrase it differently, even a dried-out “bluebottle” ought to be handled with extreme caution.

What to do if you’re stung:

As with box jellyfish stings, it’s advised to rinse the area with vinegar, followed by removing the stinging tentacles with tweezers. The aforementioned Sting No More spray or cream can be effective at treating stings (but folk remedies, such as baking soda, urine, and shaving cream, may worsen things). Ice can also be used to diminish pain. Difficulty breathing may occur in some; if this happens to you or someone in your party, seek emergency medical attention.

Sea Lice

Some people have a visceral response to the very words “sea lice,” particularly after an outbreak took place in Pensacola, Florida in the summer of 2018.

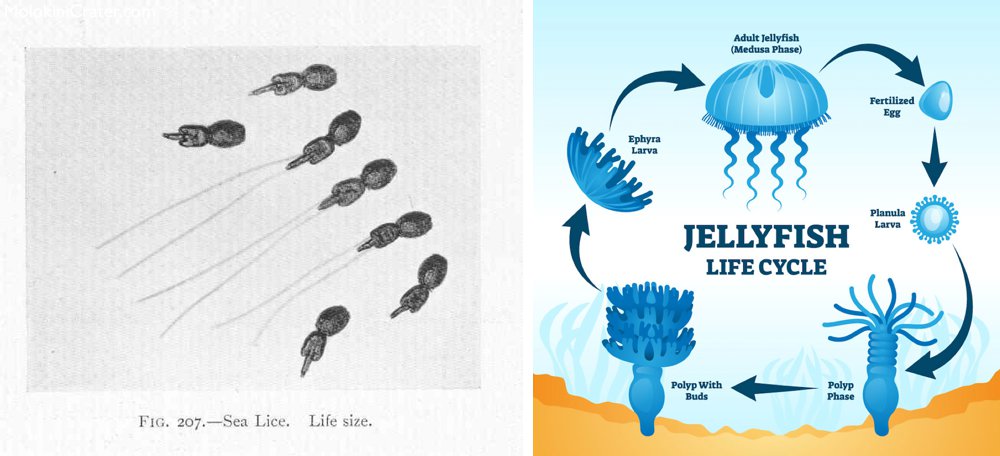

But “sea lice” is actually a misnomer—at least when it comes to the creatures that have the potential to impact humans. (“Sea lice” are small parasites that affect other marine animals.) As Amanda MacMillan reported to Health, “sea lice” was “inappropriately coined by residents who suffered strange rashes swimming in coastal waters in the 1950s.”

What are they, then? Tiny jellyfish larvae whose stings aren’t terribly dissimilar from the pervasiveness of lice: They create intense (and annoying) irritation, redness, itchiness, burning, and a rash that can last up to two to four days (but, oddly, doesn’t start for several hours—even up to 24 hours—after being in the ocean). The progenitors of these larvae are roughly an inch tall and can cause stings and pains of their own, but it’s their broods that drift around the sea and find their way into swimsuits and in armpits (and other skin crevices) that are the real nuisances. Once compressed—when the larvae find themselves trapped in a bathing suit, for example—their stinging cells fire and release toxins, thus triggering a reaction that’s technically known as “sea bather’s eruption.” As Health further reports, “The larvae also like to hang out in people’s hair, so the back of the neck—where hair hangs down and touches the skin—is a common place for lesions.” Some victims may experience a more critical reaction, including nausea, a fever, headaches, and/or infections.

Where they’re found:

Accounts are most frequently reported in the coastal US, the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean, and parts of South America. That said, reports have come in of people complaining of “sea lice” after visiting leeward beaches in Hawaii, especially in the summer months.

How to avoid them:

Though microscopic and almost impossible to see when in the water, there are precautions you can take to avoid getting stung. Eschew baggy swimwear and t-shirts when swimming, as this increases the chance of larvae getting caught and pressed against your skin. Wearing sunscreen can also provide something of a shield to keep you from getting bitten. The Florida Department of Health also recommends showering immediately after swimming (and removing your bathing suit before showering). Finally, wash your swimsuit—with detergent—after swimming in a spot that may have “sea lice” or if you’ve incurred a reaction.

What to do if you’re stung:

Over-the-counter antihistamines (such as Benadryl), hydrocortisone cream, and calamine lotion may help relieve some of the itchiness and ache that arrives, while more serious reactions should be treated by a medical professional.

With all this said, however, do know that hundreds of beachgoers swim in Hawaii waters without incident daily—and enjoy every second of it.

Hawaii Jellyfish Glass Art

The best way to see and experience jellyfish in Hawaii is at Hot Island Glass where glassblowers create stunning jellyfish glass art. Visit them Upcountry at Maui’s small paniolo town of Makawao, and enjoy live glassblowing 9-5 each day, or check them out online and have a beautiful glass sculpture to remind you of Hawaii in your own home!

Check out more Hawaii sea life with this article on the Hawaii State Fish,

The Humuhumunukunukuapuaʻa.

My Man-o-war experience happened on Kauai, on a south facing beach, very close to shore. The tentacles were very long and wrapped around my torso, arm, and hand. Needless to say, I survived! Learned the lesson you gave above, researched and found out more, and haven’t had a reoccurance. Thank you for sharing this important information!

Adolph’s Meat Tenderizer will kill jellyfish and man o’war stings. We use it in Virginia all the time. Other people use vinegar too.

Good scoop, can’t wait to get back to Hawaii and give these critters a chance to hunt me down. . . anything risk would be worth it to get back to paradise.

Aloha

Was in hawaii ( big island ) April. saw one port man of war on beach snorkeled near a reef. No issues. But had itchy rash and a couple of unknown bites each day i went snorkeling. Grew up in Philippines & Okinawa been stung by different types of jellies Vinegar or Urine has always helped. We also wore pantyhose both lower body & cut the crotch Out to.pull over head and arms Many stings were prevented.

Lifesavers at Ellis Beach Queensland Australia used to use pantihose to protect against stinging jellyfish 60 years ago when I was a teenager. Now we use full body suits when swimming or snorkelling in our district.

My kid got sea lice in Maui. Pure hell… poor little guy.

I just got home from Maui and pretty sure that’s what I have! Was mostly in South Maui but also snorkeled in Kaanapali. All concentrated inside my bra liner and lower back. Intense itching and so far no weeping or pus, but I am having a hard time not scratching. How long did your son’s last?

oh my gosh i’m so sorry. scary!

Right!?! Not fun. But, we don’t see them very often. Good to keep an eye out and be wary though.

I was in Hawaii and got stung by a box jellyfish.

Yes on meat tenderizer, but also papaya, both of which have papain, which breaks down protein….. and poisons are comprised of proteins (and peptides). A friend of mine keeps papaya skins (with papaya fruit still on them) in her freezer. When she gets stung by a scorpion, she put the papaya skin on the sting and is fine shortly thereafter.

I’ve always been fascinated by marine life, but I had no idea about the differences between box jellyfish and the Portuguese Man O’War. I’m definitely more cautious about swimming in Hawaii now, especially after hearing about sea lice too. Thanks