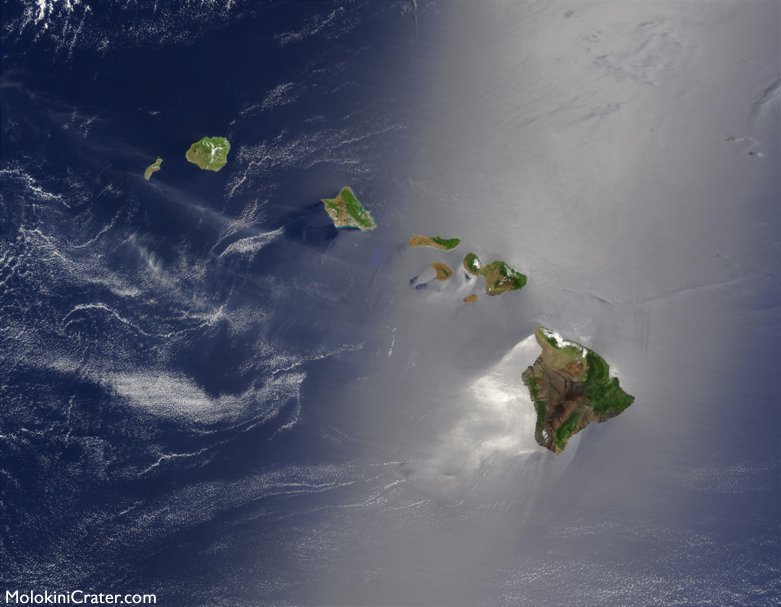

Think of Hawaii and the major players of Oahu, Maui, Kauai, and the Big Island will likely pop into mind.

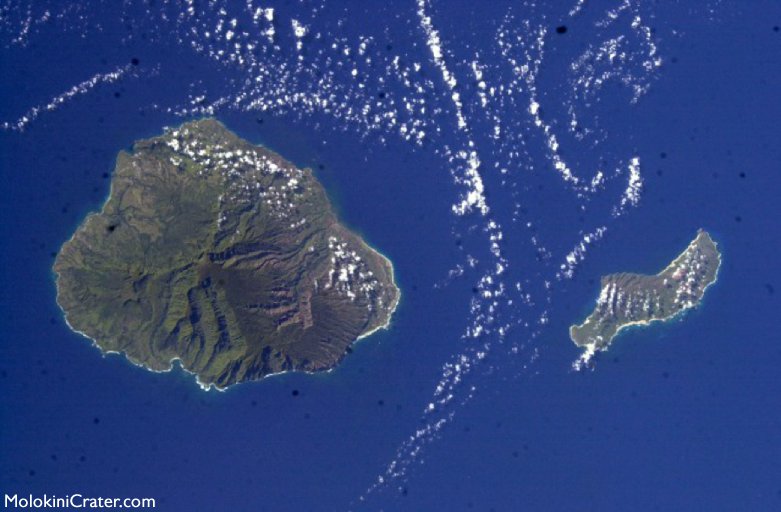

But besides the smaller islands of Molokai and Lanai, which, together with Maui, comprise Maui County, Hawaii is also home to Ni’ihau—the westernmost island in the archipelago and perhaps one of the most mysterious places on Earth.

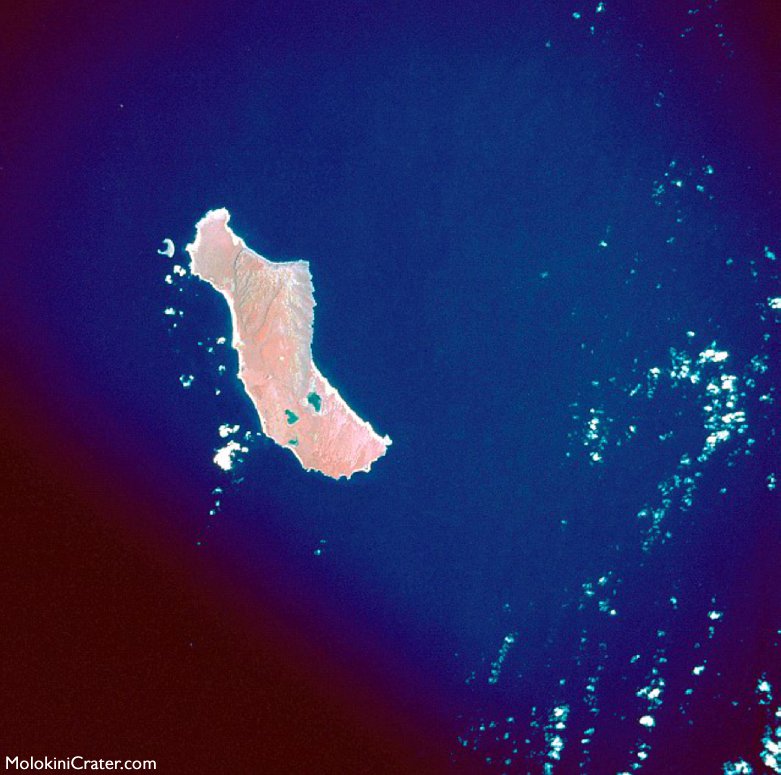

Lying less than twenty miles off the southwest coast of Kauai, Ni’ihau is aptly called the Forbidden Isle: the privately-owned haven, inhabited entirely by natives and descendants of the Robinson Family, largely prohibits outsiders. Enigmatic? Like no other.

Here’s the story behind its secrecy:

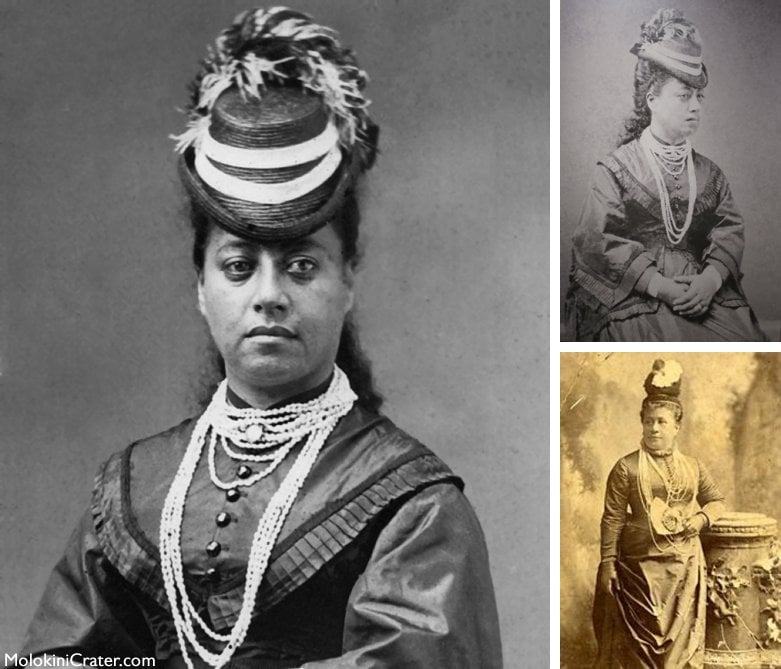

In 1864, roughly around the same time that Hawaii was experiencing the sugarcane boom that would change the makeup of its landscape for eternity, Ni’ihau moved into private ownership when it was purchased from the Kingdom of Hawaii by Elizabeth Sinclair—a Scottish farmer, plantation owner, and mother of six. The daughter of a prosperous merchant was 63, widowed, and equipped with hay, grain, a grand piano, and a single cow when she offered King Kamehameha IV $10,000 for the deed to Hawaii’s smallest inhabited island—a place that she and thirteen members of her family would ultimately almost exclusively occupy.

While visiting the island is largely outlawed, Ni’ihau officially received its moniker in 1952 when a polio plague broke out in the Hawaiian Islands. To shield the Robinson family from the epidemic, they forbade visitors to Ni’ihau and required a two-week quarantine for those who received approval to step foot on its shores. The Robinson ohana—and the native Ni’ihauans in the village of Pu’uwai—effectively dodged the debilitating disease, and the prohibition of newcomers stayed intact, as it had since Sinclair assumed possession of the 69.5 square mile sanctuary.

Comprising part of Kauai County, Ni’ihau has remained largely untouched since its earliest days of occupation. Now owned by Sinclair’s great-grandsons, Bruce and Keith Robinson, the family that purchased it ardently believes that they’re fulfilling the monarchy’s wish by barring outsiders. It’s a land for the people and by the people, with its fortuitous 200 residents working the ‘aina as those in Kamehameha’s day once had.

And such is part of its incredible allure; after all, “we want what we can’t have” became a cliché for a reason. But this is a family of conviction, denying requests by royalty, superstars, and the ultra-rich to tour its immaculate beaches and 1,200-foot sea cliffs, with visits restricted to relatives, invited guests, government personnel, and members of the US Navy.

In the mid-2000s, however, the Robinsons struck a deal with potential visitors. Helicopter excursions running from Kauai to Nanina Beach on Ni’ihau’s north shore began allowing outsiders to disembark to explore its rustic coast—the caveat being they had only three and a half hours.

Despite the brevity of the visits, guests are given a taste of old Hawaii that lingers for a lifetime: unspoiled beaches devoid of footprints, virgin forests occupied by endangered species, and a pervasive sense of being on the edge of the planet—a notion that’s not too far off the mark, considering its proximity to the International Date Line.

When Sinclair took control of the island, she made a pledge to King Kamehameha to preserve Ni’ihau’s culture and take care of its native inhabitants—a responsibility Bruce and Keith assert continues to be honored today. The island lives by the tenets of kahiki, or a traditional Hawaiian lifestyle—a manner of existence that dates back to the 1800s and brings to mind the modesty and simplicity of the Amish. Rent-control hasn’t made its way into the island lexicon, considering that residents live on the land for free. There is neither phone service nor running water, and horses and bicycles serve as the primary modes of transportation. Grass shacks offer shelter, while fish caught just off the island’s shore make up the majority of Ni’ihauans’ diet. Due to the lack of stores, supplies are shipped over by boat, solar power functions as the island’s source of modern electricity, and its residents communicate in Hawaiian—rendering Ni’ihau the only place in the world in which Hawaiian is chiefly spoken. And yet, despite the rumors that have circled—of intermarriage and people held in captivity—Ni’ihau is a thoroughly modern society: its multilingual residents bounce between their native home, outer islands, and the mainland, and often travel or live part-time on neighboring Kauai.

Remote and pristine, Ni’ihau was and remains an Eden of its own, but is nonetheless marked by hardship and tragedy.

Due to its location in the rain shadow of Kauai, Ni’ihau is notorious for its exceptional dryness. So arid, in fact, that upon his arrival on its rugged shores in 1779, Captain James Cook reported that Ni’ihau was utterly treeless—an observation that was underscored in George Vancouver’s era when its inhabitants fled to Kauai to escape severe drought and famine.

But perhaps the greatest trauma in the island’s history is the Ni’ihau Incident of the early 1940s. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, a Japanese pilot by the name of Shigenori Nishikaichi crash-landed his bullet-stricken fighter craft in an open pasture. While cautiously welcomed to the island—news of Pearl Harbor had yet to reach Ni’ihau, although its residents were aware of the tensions with Japan—the pilot conspired with one of Ni’ihau’s three Japanese residents. After a bizarre set of occurrences, natives were taken hostage as the Japanese men armed themselves, began taking prisoners, and burned the home of the Hawaiian man who had found Nishikaichi after his emergency landing. The Japanese pilot was ultimately killed and the Ni’ihaun traitor committed suicide—a tragic series of events that some speculate precipitated President Roosevelt’s decision to intern more than 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry.

But Ni’ihau has long been tantamount with harmony, and it retains that aura to this day. With no paved roads or street lights, its prodigious natural beauty shines through, while its island traditions—from the ancient art of tattooing, otherwise known as ipu, to playing the ukulele—continue to thrive. Should you not have the chance to participate in its low-impact tourism—or score an invitation from one its residents—splurge on one of their shell leis: the pūpū o Niʻihau is considered one of the most coveted and exquisite necklaces in the world.

Take the Nii Hau Helicopter trip. My family and I were in awe the entire time on the island.

How is the Robinson family related to Elizabeth Sinclair?

Through marriage. Liza Sinclair had two daughters, one of whom married an American whaling captain (Gay) and another who married the first magistrate of the New Zealand town of Akaroa (Robinson) . The little town itself has an interesting history.

At any rate, that explains why the present company is called Gay & Robinson.

The family moved to NZ in 1841 from Scotland and purchased land from the local Maori before the Treaty of Waitangi ceded the country to the British. After her husband and son were lost at sea in 1846 the by now extended family stuck it out until 1863 when they sold their NZ holdings and headed east, intending to set up residence in NW Canada but ultimately deciding on Hawaii and Niihau. They also own sizeable acreage on Kauai which they farmed in sugar cane for over 100 years.

The Gay ohana. I was told that they did hanai Hawaiian boy named Ben Kahealenu. They moved to Lanai and build their home. As Ben grew up as their servant boy on their ranch. I would love to know if the Gay ohana did bring other Niihauiians or his family.

Sorry, but just to let it be Known, Maori Never Ceded Sovereignty to the British Crown….

The Treaty was mistreated and misinterpreted by the British….who ultimately over time, colonized the Maori race .. ending with thousands of acres of land and sea resources being stolen by the Crown.

Maori are still fighting for the return of their land and resources to this day.

What is the progress on the return of their land from the illegal British confiscation what’s the current status of the Hawaiians getting their native land back in their own possession?

I used to work at the Pacific Missile Range Facility on Kauai. Spent a few nights on the island. IT is beautiful. Great memories.

Thanks for sharing, Ron! You’re one of the lucky few to visit. Any photos?

Wow! What an incredible story. I can’t imagine a place like this still exists. I am utterly fascinated by Kauai and it’s days and moon light at night are engrained in my spirit forever from my visits there. Ni ihau truly sounds like a place as close to heaven on earth as possible.