Think of seals and odds are you’ll picture the craggy coasts of Northern California or the frigid waters of Oregon’s shores.

But an exceptional breed of seal prefers sandier banks and warmer climes.

Photo and article by Maui Bike Tours

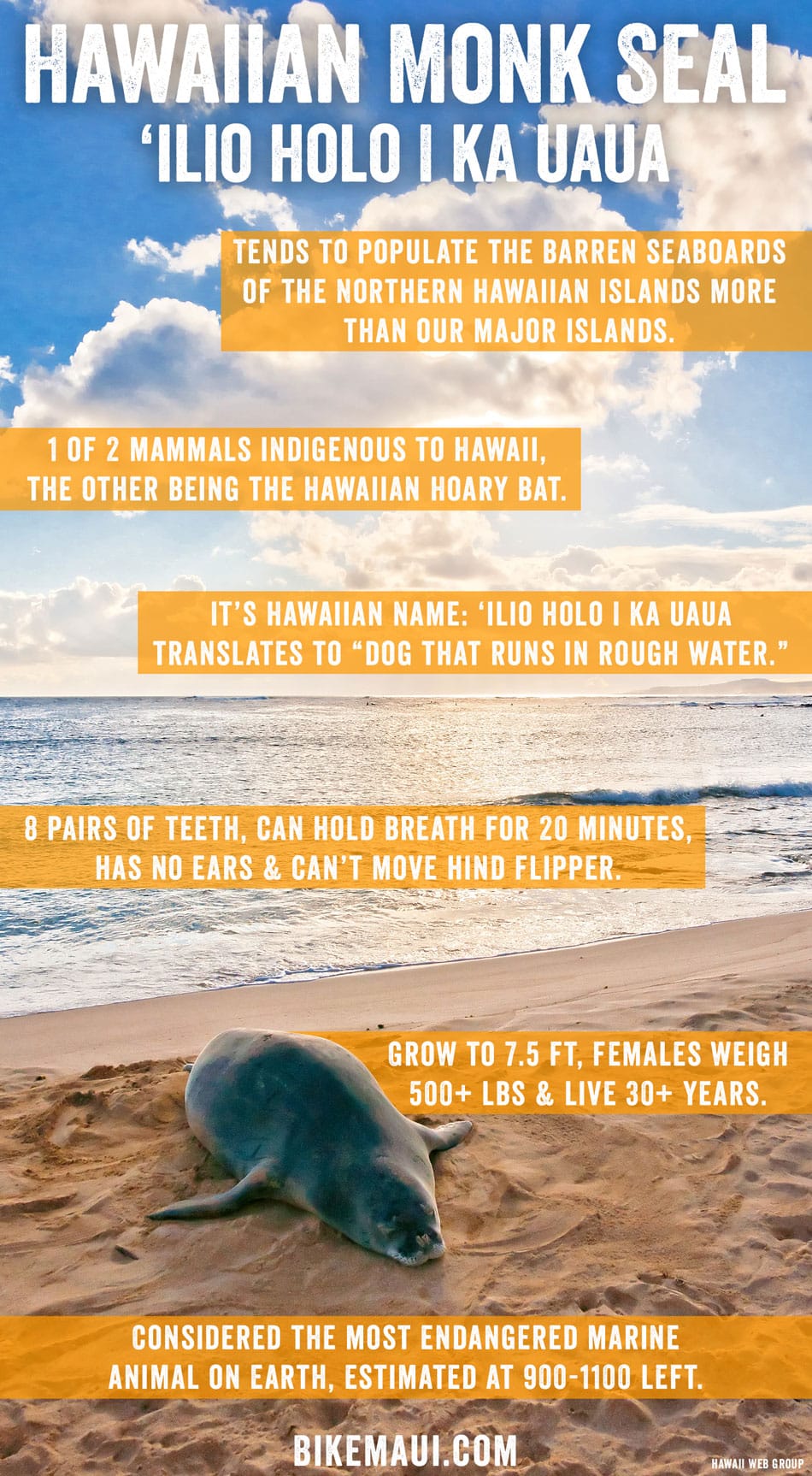

The Hawaiian Monk Seal (whose scientific name is Neomonachus schauinslandi) isn’t generally found on the major islands of the Aloha State but, rather, populates the barren seaboards of the Northern Hawaiian Islands—a set of small islands and atolls off the coast of Kauai and Ni’ihau that’s home to some of the world’s rarest and most exquisite species. Occasionally, they’ll visit Molokini Crater, but often they’re taking naps on quiet beaches around Maui or out to sea.

One of two mammals indigenous to Hawaii—the other being the Hawaiian Hoary Bat—the Hawaiian Monk Seal earned its moniker because of its appearance and behavior: pleats of skin that resemble a monk’s cowl and a proclivity for traveling solo or in small groups. (Even when they are near each other—basking in the sun or lying on the sand—they don’t touch each other, thus giving more credence to their given name.)

Called ‘ilio holo I ka uaua by Hawaiians—which translates to “dog that runs in rough water”—the Hawaiian Monk Seal impresses and beguiles.

The mammal grows to an average of seven and a half feet but its females weigh between five hundred and six hundred-plus pounds, rendering it one of the largest aquatic animals in the Pacific. It maintains its formidable size with a steady diet of foods found in the coral reefs of Northern Hawaii: spiny lobsters, eels, squids, octopuses, and fish, all of which are consumed with eight—yes, eight—pairs of teeth. (Indeed, this is a fertile oasis. Hawaii’s endemic species may be limited, but the Pacific marine life near the Hawaiian Monk Seal’s territory boasts 680 varieties of sea fish and 450 varieties of reef fish—to say nothing of the sharks, eels, whales, and turtles that roam these remote parts.) And while the Hawaiian Monk Seal typically dives underwater to forage food for an average of six minutes, it can hold its breath for up to twenty minutes at a time.

One of two remaining monk seals on the planet (the other is the Mediterranean Monk Seal, whose population is less than 700), the Hawaiian Monk Seal belongs to the Phocidae kin.

This earless or “true” seal tribe is distinguished by an incapacity for moving its hind flipper and its conspicuous lack of ears. It’s also notable for its slippery body—the fur of which is shed in an annual catastrophic molt, wherein seals cast off the top layer of their skin and hair. And while the Hawaiian Monk Seal prefers to stay close to Hawaii’s perennially sunny shores, those that spend an extensive amount of time scavenging in the sea eventually grow algae on their fur, which gives them a green, iridescent hue.

Despite a growing number of people who believe that the mammal isn’t a veritable Hawaiian, the Hawaiian Monk Seal is believed to have been splashing through the Pacific of Northern Hawaii for several million years. With an average life span of thirty years, females reproduce roughly every two years; mothers nurse their offspring for an average of six weeks, during which time they essentially fast so as to not leave their pups unattended, losing an astonishing third of their body weight.

In spite of their long history in these revered waters—and the lengths mothers take to shield their children—the Hawaiian Monk Seal has been radically decimated; today, they’re considered the most endangered marine animal on Earth.

That decimation began when ancient Polynesians first arrived in Hawaii.

The animal was an effortless mark. Enormous, largely passive, and slow-moving, they were harpooned for meat, oil, pelts; even scared off by the Polynesians’ dogs. By the 19th century, they were hunted to near-extinction, while fishermen began slaughtering the animal because of its large consumption of fish. Presently, only two out of ten pups born in the main breeding colony of the French Frigate Shoals survive their second birthday; as a whole, the mammal faces a number of threats, from invasive species and overfishing to rising sea levels. And even though the Hawaiian Monk Seal is primarily found in the Leeward Islands, approximately 150-200 have migrated towards the main islands and starting having pups—thus giving way to the rare but not unfathomable possibility of seeing a seal sunbathing on one of Hawaii’s famed beaches.

But such propagation hasn’t taken the Hawaiian Monk Seal off of the endangered species list. Estimations vary, but it’s believed that no more than 900-1,100 Hawaiian Monk Seals remain in existence. In a federal project that will ultimately cost $378 million and require 54 years, efforts have been put into place to keep what’s left of this species alive and on the uptick towards thriving.

Part of that is accomplished through what’s come to be known as “seal protection zones.” Helmed by volunteers for the federal government’s “Monk Seal Response Network,” these precincts are taped off and watched over by a team of helpers when a seal is spotted offshore, thereby keeping the scarcely-seen animal safe from beachgoers. And while a slew of suspicious deaths have occurred from Molokai to Kauai, during his tenure, President Obama expanded the size of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in northwestern Hawaii to more than half a million square miles—in other words, double the size of France. This space, protected from all but recreational and subsistence fishing, is deemed one of the surest ways that we can safeguard our waters and ocean animals from human disturbances and climate change.

All of which is a boon for the creature—and for its many admirers.

Sightings may be erratic—the Hawaiian Monk Seal spends a third of its life at sea—but those who do spot one are given an exquisite treat. This, after all, is a mammal who can dive over fifteen hundred feet to feed on crustaceans; who, as the oldest species of seal left on the planet, is considered an ancient living fossil that may provide key clues into the evolution of the planet—and the fascinating, critical marine life that inhabits it.

Several years ago I was snorkeling, I believe it was around the Salt pond area, an a monk seal showed up. The other people were intimidated and got out of the water. I saw a plastic bag that someone had left from feeding fish and I didn’t want to leave it out there so I swam towards the bag. The seal followed me but I didn’t feel threatened. I’d never heard of them attacking people. She (or he)was huge and followed me which ever way I turned but I stayed calm to get that plastic bag. When I got out my family was very excited because they video taped the incident to show the situation. Very thrilling experience and so glad I got that bag cause I know how it could have been. Wish people wouldn’t leave that stuff behind.

We were fortunate to see a monk seal swim by our 11th floor lanai on our last day of our first vacation in Maui last May. At first I had thought it was a very large honu, but when looking through binoculars, it clearly was a seal. It had been a disappointing day, as we got closed out of a tour we really wanted to do, but seeing this monk seal more than made up for that and I was thrilled!

Have been seeing them more frequently on Maui in the last 3-4 years have seen them in Kapalua bay,S turns,south Kaanapali beach,Makena and Hookopa. We respect them and keep our distance always cool to see.

In February of 2019, we saw a monk seal sunbathing at Keone’o’io Bay (La Perouse Bay). He was just sleeping peacefully on a rock. Such a delightful treat to see him there and even moreso now that I realize their limited numbers.

Hawaiian monk seal (F3/RH 44) enjoys sushi for lunch!

This video of an endangered Hawaiian monk seal (Hawaiians call the seal `Ilio holo I ka uaua, which means, “dog that runs in rough water”) catching, playing with, and eventually eating an octopus was shot off the lanai (porch) of the 2nd floor of Hoyochi Nikko condo on the Lower Honoapiilani Rd by Lahina in Maui, Hawaii in February, 2010. Some internet digging suggested there may only be between 500 and 1000 of these exquisite mammals left. Obviously, they enjoy octopus! From what we read, the seals are marked with hair dye which is why we (with binoculars) were able to clearly identify the F3 on her back. A Dr. Leisure video posting said this seal is tagged as RH44 with a dye marking of F3. If you search, you can find another video of this same seal. When I started shooting this, she was swimming leisurely so I decided to zoom out and do a slow zoom in on her, but when I realized that she had hit something, I zoomed in quickly. (Video shot by Ann Thompson.)

https://youtu.be/z9X8JeXy_oE

We’ve been lucky enough to see one on each of our two trips! Both along the Honoapiilani highway between Lahaina and Ma’alaea. Both times they were sleeping up on the small beaches in the evening not long before sunset. In 2017, I caught something out of the corner of my eye and we pulled over. In 2019 we did keep an eye out for them and saw one on our last night on the we were on the Island. They are huge, very cool creatures.

When at home on Maui last Dec 2018 my sister & I went to Hookipa (one of my favorite beaches as a kid). I saw a coned off area & noticed an animal lying on the beach. There was a volunteer watching over it from outside the coned area. She told me it was a monk seal & since the tide was rising it would probably move further up the beach. I’d never seen one before. I asked her why it chose that beach. She said it was born on Molokai & so was it’s mother but they came regularly to Hookipa. The animals are tagged so they’re able to track them. If you think about it there are many beaches between Molokai & Hookipa yet it chose to come there. Then the seal moved up the beach probably 10-15 ft as the tide changed. I was so startled but managed to take still photos from my distance, didn’t know how to take a video. It was an amazing experience

I think I saw one on March 27th at Ho’okipa beach. It was sleeping on the far right side of the beach along side 4 turtles. I couldn’t get a good look at its face so I don’t know if it is a monk seal or another type of seal. Are there other animals here that look like monk seals? Other seals? Sea lions?

Observed from the 6th floor balcony, Lahaina Shores Resort, Dec. 31, 2022 approx. 10:00 am. Swimming north parallel to shore about 15 ‘ west of the sand/coral line. Water depth guess-4-5’. Appeared longer and bulkier than a large human. Dark color, slightly greenish. Traveling slowly seeming unfazed by presence of a few people in the water within approx. 25’.