The shores of Maui are often synonymous with Humpback Whale sightings. And while these magnificent creatures are well-worth the decision to book your Hawaiian vacation during whale season, the waters off the island’s coasts are also home to an equally captivating mammal: The Hawaiian spinner dolphin.

Called nai’a in Hawaiian, –and throughout the Hawaiian Islands.

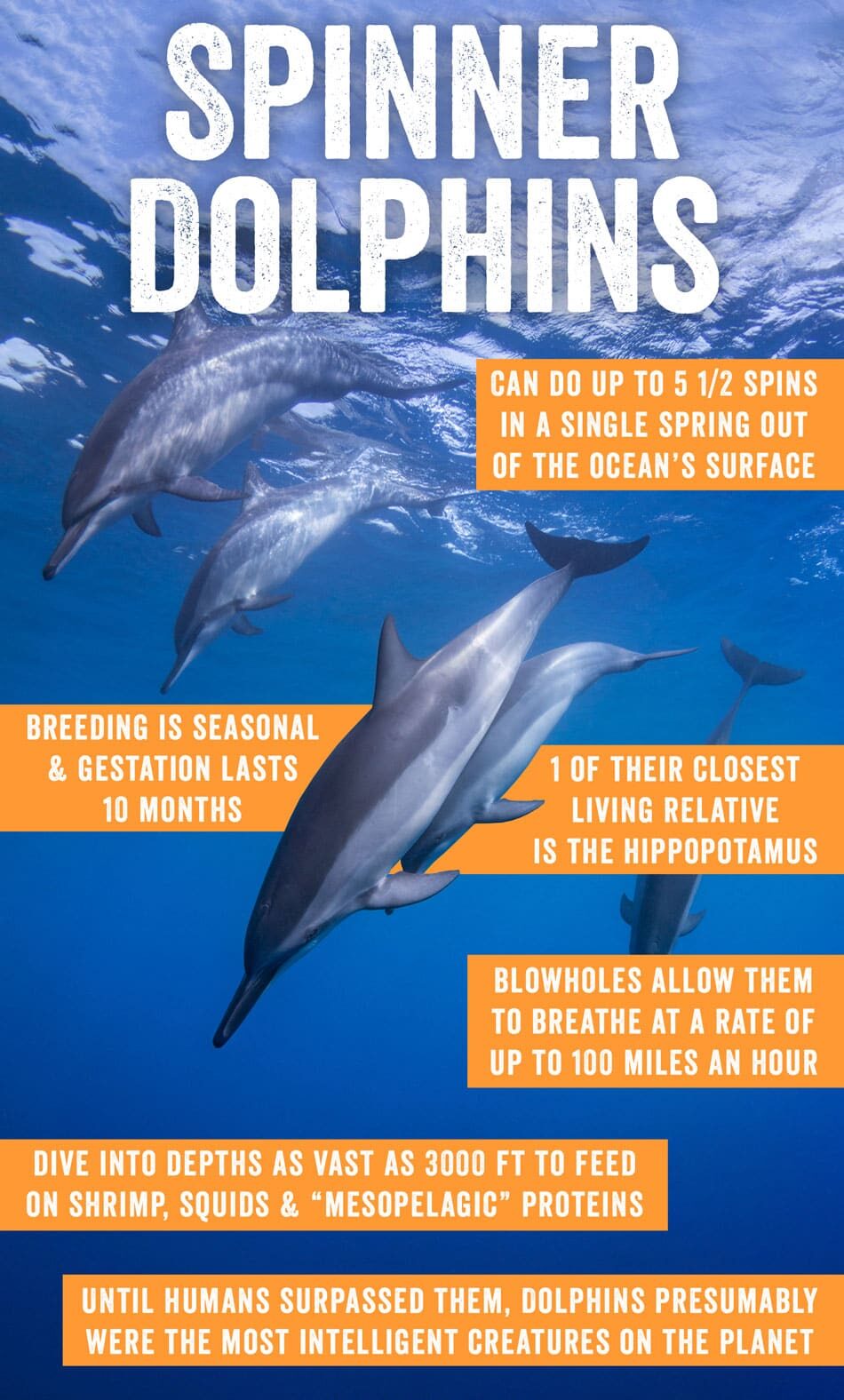

These beauties belong to the Delphinidae family, a group of marine mammals that comprises toothed whales. One of the spinner dolphin’s closest living relative is the hippopotamus—the pig-like amphibian we often associate with the waters of West Africa.

Hawaiian spinner dolphins diverged from their hippo ancestors more than forty million years ago when they returned to their aquatic environments, and the limbs they used on land—like a hippo’s feet and toes—evolved into flippers. Meanwhile, their once wolf-like teeth were modified to smaller pegs as the ocean cooled and the food supply shifted.

Those flippers have taken them far.

Hawaiian spinner dolphins operate much like insomniacs who forage the fridge in the middle of the night for sustenance. When night descends on the Pacific, they dive into depths as vast as 3,000 feet to feed on shrimp, squids, and “mesopelagic” proteins—like lantern and cuttlefish—that roam in the mid-zone of the ocean. These brainy mammals, who have telltale white bellies, use echolocation to, in essence, tell their friends where to find food sources. Using signature whistles and what’s known as burst pulses, the small groups also unite to forms lines of defense, particularly to ward off the sharks to which they’re vulnerable.

Such susceptibility may be one of the reasons dolphins spend their daylight hours in the bays off our sunny shores. As dawn turns to morning, schools of dolphins often regroup. Fueled for fun, they make a charming spectacle in the water—rubbing and sliding against one another with affection, diving underneath their cousins, even playing patty-cake with each other.

When playing subsides, these schools nestle together to rest.

And literally so: The school tightens up and orchestrates its collective breathing, while the guards of the group—adult and teenage males—move alongside their female counterparts and children. To humans, this appears as a school rising and falling from the surface in a union so lovely it appears to be choreographed (it is).

But as human-like as dolphins may appear—having a sensitive set of social skills that rivals most adults—their sleep resembles ours only a bit.

Dolphins rest only one part of their brains at a time as part of a process called “unihemispheric slow-wave sleep,” in which half of their brains remain alert (and thus, on the lookout for impending danger, as well as to control breathing patterns and generate enough energy to stay warm in the ocean waters). Given that they rely on sonar for “seeing”—the precision of which is nothing short of amazing—when the sonar shuts off, they rely on their vision as they doze, much like an exhausted child who has fallen asleep with their eyes open. And indeed, this is true to some extent: Their binocular eyes function independently of each other, with one eye closing while its side of the brain sleeps and the other stays open.

The bonds formed between dolphins are unlike any other on Earth.

Dolphins possess a sophisticated paralimbic system that processes emotions, which some hypotheses suggest may be vital to the profound social attachments that exist within their communities.

Dolphins live in what’s thought of as an open and loose social organization, much like young adults in the free-loving hamlets of the 1960s. Individual dolphins may occupy—or attend—different schools on a daily basis, while our subspecies in the Hawaiian Islands shape family groups while also associating with other ohanas. And the virility of “spinners” isn’t just a myth: Their mating system is what we would deem promiscuous, with some individual dolphins switching up partners every few weeks, while others form pairs or trios that can last for decades.

Breeding for Hawaiian spinner dolphins is seasonal; gestation is a ten-month-long process.

When a calf is born—tail first—it stays close to its mother’s side, suckling for up to two years and following their slipstream in the water—first, near the head; a week later, close to their dorsal fin. This arrangement is known as echelon swimming, which scientists suggest is the oceanic form of carrying an infant.

Their names are far from an accident:

Indeed, one of the most distinctive facets of spinner dolphins is their facility to pirouette in the air, with most accomplishing five and a half spins in a single spring out of the ocean’s surface. Tail slaps, flips, and “salmon leaps”—slightly arched jumps that resemble a salmon vaulting up rapids or falls—are also part of their ocean tango.

As joyous as all this leaping and twisting may sound, there’s a reason behind their exhibitionism: Spinning in the air enables the dolphin to reach greater depths when they break the water (thanks to the weight of their bodies, which plummets them deeper under the surface), explaining why schools of spinners use these “acrobatics” while herding fish at dusk. At other times, spinners, well, spin because they’re signaling to their companions where they’re headed; others utilize these leaps to shake themselves free of parasites.

Spinning aside, one of the most fascinating aspects of the Hawaiian spinner dolphin is the manner in which they breathe.

Blowholes located at the top of their heads allow them to breathe at a rate of up to 100 miles an hour. And such rapid-fire breathing doesn’t require them to completely surface from the ocean, in that a bubble bridged between air and sea permits them to take in oxygen. To illustrate this further, when they’re not feeding, they remain close to the surface, during which the flap of skin that comprises their blowhole opens and closes under their direct command (unlike humans, for whom breathing is involuntary).

That oxygen isn’t just essential for their brilliant physical movements: It’s also key for their incredibly powerful brains.

As the National Geographic reports, “Until our upstart genus surpassed them, dolphins were probably the largest brained, and presumably the most intelligent creatures on the planet…Pound for pound, relative to body size, their brains are still among the largest in the animal kingdom—and larger than those of chimpanzees.” Such terrific intelligence has led many to theorize that our “Ambassadors of Aloha” have an ocean language that’s as complex as humans and apes—one, in fact, that empowers them to eavesdrop on other groups about potential prey, identify friends for decades, communicate gesturally, and invent a signature name for themselves upon birth and hold onto it for their existence—rendering dolphins the only animal on the planet besides humans to have specific labels for themselves.

Here in our pocket of the planet, Hawaiian spinner dolphins tend to swim, rest, and frolic off our sunniest coasts.

But despite venues that advertise “swimming with dolphins,” know this: It’s illegal to interact with them beyond viewing their beauty from the lip of a boat. As it should be: This might be one of the rarest and most extraordinary creatures of not just Hawaii, but also of the universe. Next time you see them on the way to or from Molokini, count your blessings!

Love this article. These creatures are part of the reason why I love my Hawai’i nei.